KARACHI’S STREET ECONOMY

Fruit vendors and other hawkers at a bazaar in Karachi | Courtesy the writer

This article draws upon the work I have done at different times with Architects Asiya Sadiq Polack and Christophe Polack, Dr Noman Ahmed, and Engr Mansoor Raza, and various researches on the subject I have carried out with the support of the Karachi Urban Resource Centre, Hamza Arif and NurJehan Mawaz Khan.

Hawkers are everywhere in Karachi. They dominate the urban landscape, except in the cantonments where they are prohibited. Karachiites of all classes in the city deal with them.

My association with them began in 1986 while travelling through Somerset Street with my teacher, Ghulam Kibria. I saw hawkers being removed violently from the pavements of the street. Their carts were being overturned, they were being thrashed by batons and attempts at confiscating their goods were also being made.

Kibria Sahib, a much celebrated engineer and humanist, was horrified. “You don’t treat your own people like this. The unmet needs of the stomach are responsible for so much evil.”

He then suggested that I draw up a plan which we could place before the Commissioner of Karachi, whereby hawkers’ zones could be created and regularised. Over the next few months I interviewed the hawkers, government officials, residents of Saddar and transporters, and drew up a plan for the pedestrianisation of certain streets in Saddar, where hawkers could be located. I took the plans to Ghulam Kibria and he said that, before taking it to the officials, we should present it to the hawkers, residents and the market operators.

The city’s informal economy employs 72 percent of its entire workforce and is the engine that keeps the city going, helping people survive even during periods of severe economic downturn such as now. Hawkers form a small part of a huge street economy, but are vital to its processes. Can the city survive by uprooting them? Can it afford to ignore them?

When we presented it to them, they all tore the plans to shreds and I realised that even participatory research findings can lead to the wrong recommendations and a misunderstanding of the conflicting interests of the different stakeholders. So, we did not take this study to officialdom and the matter was closed.

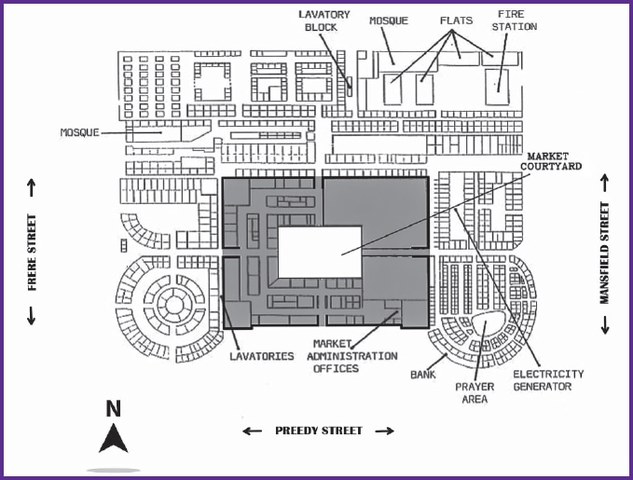

However, my interest remained alive and, after the formation of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in 1989, the centre carried out a number of surveys in 1995-96 which showed that four streets in Saddar paid a bhatta [protection money] of 10.5 million rupees a month to “someone” who was supported by the police. The URC also documented the process and the actors involved in the collection of bhatta. The bhatta issue attracted a lot of attention and tickled the curiosity of the media and its audience. So the URC decided to study in detail the street economy phenomena in Karachi, with a focus on Saddar. The study was carried out by architects Asiya Sadiq, Christophe Polack and myself, with support from the URC.

The study took two years to complete and looked at various relationships the vendors had with each other, their suppliers and the manufacturers of the goods they sold, government agencies, transporters, their customers, and those who extracted bhatta from them. This study resulted in a book The Hawkers of Saddar Bazaar: A Plan for the Revitalisation of Saddar through Traffic Rerouting and the Rehabilitation of its Hawkers. It also established a strong relationship between the URC and the hawkers, which has stood the test of time.

Government officials such as Engr Zia-ul-Islam, then head of the Traffic Engineering Bureau, helped the study with his expertise and previous research. The findings and recommendations of the study were presented before (the late) Mayor Naimatullah Khan, who was very supportive of it, but wanted hawkers legalised in certain areas but removed from the precincts of Saddar.

The study taught us that vendors were a small part of a huge street economy that consisted of formal and informal manufacturing, raw materials suppliers, wholesaling (local and imported supplies), retailing, transportation, formal sector shops and markets, and various types of service provision to the actors of this economy. This paper looks more at the retailing aspects of this economy in relation to Saddar.

Keeping this understanding in mind, a new study was initiated in 2018. This study was carried out under the supervision of Dr Noman Ahmed, Engr Mansoor Raza and myself. Its focus was on various areas of District South. The methodology adopted for the study was to look at the situation of the vendors and relate it to the processes and actors involved. The analysis was based on 14 points developed by Dr Noman Ahmed.

In addition, mapping of locations in the study areas of the street economy, and the scale and nature of businesses was documented. Their supply chains along with their relationships with hawkers, government agencies, customers and formal sector enterprises with each other were identified. The impact of the Supreme Court-ordered demolitions on the street economy were also investigated. Observation was an important part of the research, along with hundreds of conversations and detailed interviews of 182 hawkers, formal business owners, customers and trade organisations.

FINDINGS

The street economy is the retailing of skills and materials, manufactured and supplied through different formal and informal processes, to retailing enterprises working informally from state or privately-owned spaces.

This economy is a part of a larger informal economy, which employs 72 percent of Karachi’s workforce. There are 202 markets in the formally developed commercial areas of the city. Wherever you have these formal markets, you have an active informal economy around them, which serves the functions of the market at a cheaper cost than the formal shops and makes them affordable to the lower-income groups in the city.

The commercial areas and the formally developed markets in them have been built by the Karachi Development Authority (KDA), the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC) and Cantonment Boards. Almost all of the Central Business District and Saddar have informal markets along most of their important roads and neighbourhoods. Because of the visitors that these markets attract, their precincts become major transport hubs and this increases customers for the vendors. But this also creates congestion and often traffic jams.

All of the city’s informal areas also have an informal street economy. These markets are very close together as they are mohalla markets to which the residents (especially housewives) can walk easily.

It is estimated, through observation, that the majority of hawkers in Karachi are located in these neighbourhood markets in low-income areas. Many of these neighbourhood markets began at bus stops and, as they expanded, they were accepted as markets by local governments and provided with the necessary facilities. In some cases, formal market buildings were constructed to accommodate them.

The non-availability of toilets and portable water have remained a very major problem for the vendors and visitors to these markets. Informal food outlets are an important part of these markets and the media has often raised issues regarding hygienic conditions in food retailing.

THE PREFERENCE FOR HAWKERS

The hawkers are preferred to formal sector shops by low-income and lower-middle-income groups. The main reason for this is that the poorer sections of society feel closer to them. Many respondents said that shopkeepers intimidated them and also that they were not very responsive to bargaining. Another factor was that hawkers’ goods were about 15-20 percent cheaper than that of shops.

It was also mentioned that hawkers are located at transport hubs and so they are easily accessible to commuters, who on the way home, can pick up household requirements without having to walk long distances. A few customers also mentioned that, over the years, they had developed relationships of trust with the hawkers they regularly purchased from and, as a result, credit facilities were also available to them. In one case a marriage between the hawker’s daughter and the customer’s son was also the result of such relationships.

Most of the shopkeepers interviewed liked to have hawkers in front of their shops. Because of these hawkers, there appeared to be life in the street and this attracted people to the area and hence to the formal shops as well. Many shopkeepers had business arrangements with the hawkers as well. These worked both ways. Items not available but in demand were exchanged between the hawker and the shopkeeper to the benefit of both.

For hawking to be successful, the area in which it takes place has to be clean as well. For this purpose, hawkers get together to employ “sweepers”. Every morning and evening, when the shops close down, the pavements are cleaned and the waste lifted. The sweepers are paid between 10-20 rupees per day per hawker and usually cater to about 35-50 hawkers.

Empress Market before and after the demolition process | Owais photos; courtesy Urban Resource Centre

In addition, they also employ security guards for the protection of their merchandise at night and, where relations are good, their merchandise is stored in the shops in front of whom their cabins are located. The security guards are paid 20-50 rupees per day by each hawker and they are sometimes shared by the formal sector shops as well.

There are all types of hawkers. There are those who place their wares on a cloth spread out on the street. There are those who use three-wheeled wheelbarrows. The most popular is the four-wheeled cart or thela, which is either owned or rented. There are also small kiosks. At times they have been set up by the government.

The pavements also have beggars, performers, fortune tellers and musicians. They all pay bhatta to the police. The most popular performance is that of parrots picking up tarot cards and telling your fortune. All these relationships point to a strong social construct between the players in the street economy drama.

Interviews with hawkers showed that the vast majority of them set up businesses as near as possible from their homes so as to save costs and the inconvenience of transport. The main areas which they occupy are pavements, roadsides where pavements are not too narrow, bus stops and transport terminals, pedestrian bridges, under those flyovers which are serviced by transporters, and around formal sector markets.

To secure a place, a new hawker has to seek the permission of the other hawkers in the area or, where policing is strong, has to seek the permission of the local government tout.

They may also be invited by a shopkeeper to install themselves before his shop. But in this case, again, the agreement of neighbourhood hawkers is required. After the initial bribe, local government touts and police collect an amount of 500-1000 rupees per day from each hawker.

Most of the hawkers interviewed said that they take to hawking because they have no other job option. There were also those that had lost a job because of a layoff in industry or government. Others have a preference for it because it can be an evening part-time job, while they work elsewhere in the day time. This helps them beat inflation and recession.

Setting up a hawking business requires a small capital investment of about 20,000 rupees. This is not difficult to borrow. However, a majority of respondents preferred government or semi-government office 9-5 jobs, since they provide them with greater respectability both in their families and their social groups.

The street economy expands enormously during Ramazan, Muharram and other national or religious holidays. This it does often without permission from the state. Food stalls are set up along, with retailing of different types of merchandise. The gates to parks and public spaces visited by Karachiites are crowded with food retailing hawkers and so are the beaches. At Seaview beach, the right of subletting space at a cost is given to a contractor who bids for it from the Defence Housing Authority (DHA). In Ramazan, night cricket, complete with lights, is organised by residents, which increases their clientele.

There are many vendors’ organisations, some of whom claim to be registered. However, they only come together in a crisis; otherwise they are dormant. The street economy also caters to the Urs of saints at shrines in Karachi. This involves the setting up of kiosks for the sale of chadars, flowers and a large variety of trinkets. Extra space is also occupied for the preparation of deghsand a large number of thelas around the entrance to the mazaars and the streets adjoining them. There is no estimation of how many people visit the mazaars, but the media talks of thousands of people visiting the Urs of Ghazi Abdullah Shah and Yusuf Shah. We have no estimate of the scale of the economy that these festivals generate.

HAWKERS AND GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

Local government has historically not only supported hawking but has also built a large number of kiosks and rented them out to small enterprises. These have been constructed on pavements, roads and open spaces around various markets. This was done by the Ayub government to overcome unemployment and poverty.

Similar kiosks and permission to hawk was also given for other markets such as Lea Market, Soldier Bazaar Market and Bolton Market (which was ultimately demolished for the construction of a larger market). The number of such shops and “encroachments” is well above 20,000. Over the years, the government has planned many demolition and relocation schemes for the hawkers, and their implementation has been attempted. However, the street economy has always come back through demonstrating and negotiating with an understanding government.

The tradition of accommodating hawkers was also supported by our two elected mayors, Naimatullah Khan and Mustafa Kamal. Both of them promoted bachat bazaars and allocated space for them. Both of them established cabins and small shops on the pavements of the city, which paid rent regularly to the local government through bank deposits.

The location of these cabins and shops (such as bus stops and busy markets) were conducive to the promotion of small enterprises. Both the mayors were not anti-hawkers per se, but they wanted them registered and legalised in specific locations which did not hinder traffic and pedestrian movement, or create an unpleasant “social” environment.

The relationship between the street economy and officialdom has been closer during periods of empowerment of local government than during bureaucratic rule. In any case, local government representatives or the civic agencies have very little dealing with the street economy apart from negotiating location and bhatta.

ENTER THE SUPREME COURT

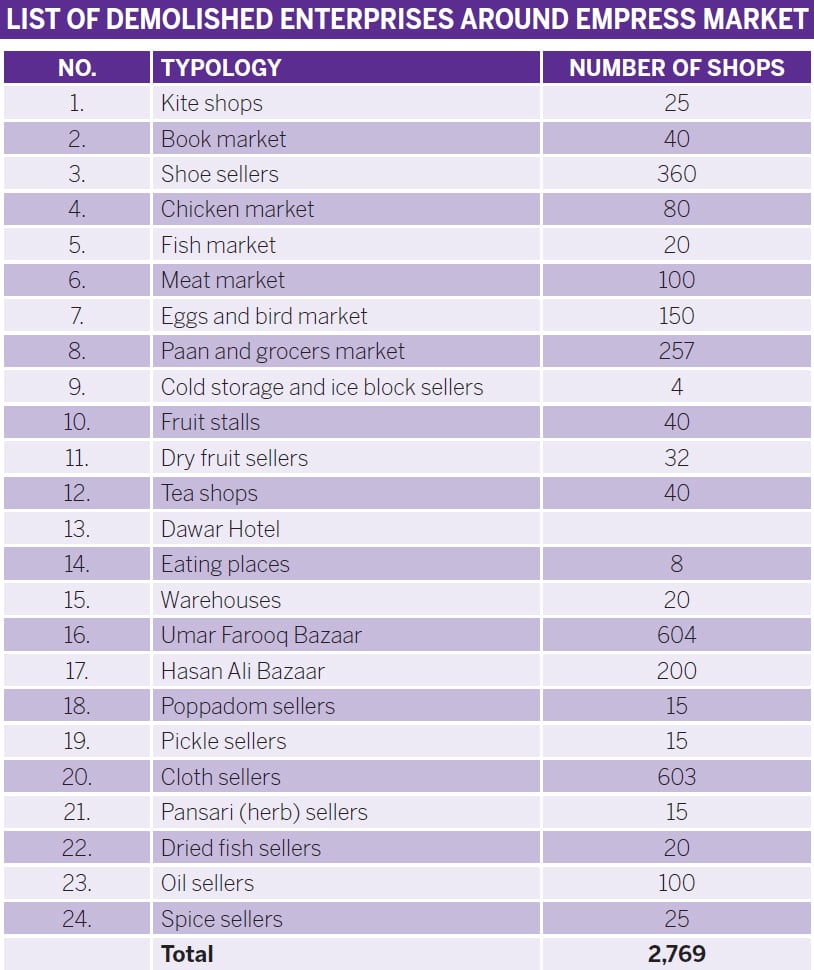

Approximately 4,000 hawkers were removed from the Empress Market during the demolition

In October 2018, the Supreme Court of Pakistan ordered the removal of all street activity that was obstructing pedestrian and vehicular movement in Karachi and also within the market buildings.

It also ordered the demolition of all structures that violated the 40-year-old Karachi Master Plan. This was followed by a Sindh High Court judgment of October 29, which ordered the removal of all informal street activity from main roads and crossroads.

According to an Urban Resource Centre survey, these decisions resulted in the demolition of 3,495 shops and the removal of approximately 9,000 hawkers, including 82 women hawkers, from the Empress Market. These displacements led to a loss of jobs to shop owners, hawkers, porters at the markets, security guards and sweepers. Many of them could no longer keep paying the rent for their homes, while most of them had to borrow money and fell in debt. Many of those spoken to complained of deep depression. However, the most serious result of this displacement was the discontinuation of the education of a large number of students. The vendors were further devastated by Covid-19, and some complained that they had to beg for the first time in their lives.

Major losses were also suffered by the food chains, where crores of rupees of dry fruit, tea, eggs, vegetables and other dairy products had been paid for but could not be distributed. In many cases, the spaces where they had been stored were demolished while the products were still stored in them.

It is pertinent to mention here that wholesalers import millions of rupees of dry fruit from Afghanistan, tea from Sri Lanka and Kenya, and exotic animals and birds from Latin America and Southeast Asia, which they pass on to retailers at the kiosks and cabins of specialised markets within Saddar.

Fruits and vegetables from the sabzi mandi were not collected for retailing in the hawkers markets. It is reported that they also rotted at the sabzi mandi or in piles in the areas where hawkers were previously located. In addition, container-loads of used clothes are imported from Western countries to Pakistan and they are sold on thelas, cabins or shops in the city. They are the main source of cheap clothes, especially warm ones, for the lower income citizens of Karachi. Additionally, electronic and household goods smuggled back from the Afghanistan transit trade are sold on thelas at the various Sunday markets in the city including on Muhammad Ali Jinnah Road.

Leaders of the Empress Market Fruit and Vegetable Association hired a lawyer and filed a petition in the Supreme Court against the demolition process. However, it was dismissed. Meanwhile, the government promised an alternative location to the rent-paying and/or leased shops, which were no more than 20 percent of those that had been demolished. In the majority of cases, the dislocated enterprises discovered that the properties that were being allocated to them were already occupied or they were in locations where businesses could not function because of a lack of visitors to the area.

According to the leaders of the various businesses, the anti-encroachment drive was successful, unlike before, because it was backed by the Supreme Court, which made negotiations with the local government impossible, and because the Rangers instead of the Police were responsible for maintaining law and order. They also claimed that, unlike before, the climate of fear in the country prevented them from large scale agitation and that large sums of money were paid to the vendor leadership to keep quiet.

Another group that was interviewed was of customers and transporters. Customers said they could not find their regular vendors and had to look for new ones. Also, whereas earlier, everything was available in one location, now everything was spread out, resulting in loss of time and inconvenience. Tea shops and canteen owners also lost customers and so did transporters as commuters in Saddar declined by 50 percent.

We are not aware of how all this affected manufacturing at Lalukhet or Shershah, but the making of flowers, trinkets and food at home, which are the job of women and children, were badly affected.

An analysis of all of Karachi’s street economy is not possible. However, it is estimated that 2,000 shops and cabins and 4,000 hawkers were removed in Saddar (see table below). At a daily earning of 1,000 rupees per day, their total earnings amount to 2,190 million rupees per year. At a modest estimate, there are 150,000 hawkers in Karachi and, at 1,000 rupees per day, their earnings amount to 5,475 million rupees per year.

About 50 percent of the hawkers have come back to Saddar but not to their original locations. They claim that their earnings have been reduced by 50 percent and they have lost their old customers. A large number of them demonstrated in front of Empress Market on December 19, 2020, claiming that Saddar and Empress Market belonged to them. This raises the issue of heritage.

THE HERITAGE ISSUE

The Supreme Court, in its judgment and orders, mentions only the Empress Market, although there are other heritage markets as well such as Hoti Market, Lea Market, Soldier Bazaar Market, Cantonment Market and Jackson Market. The systematic removal of shops was only carried out at Empress Market and, half heartedly, at Lea Market.

Empress Market was a meat and vegetable market where you could get every household item under one roof. When it was built in 1889, it had 280 shops. In 1954, this was increased to 405 shops and stalls who paid rent to the KMC. Soon after, KMC built 1,390 cabins around the Empress Market, which have been removed as the result of the anti-encroachment drive of 2019. Inside the Empress Market, only 19 shops are left.

Indications from the government and media are that the market will be converted into a high-end dining space, a museum or an art gallery. The government’s contention is that internally the market had to be cleared because it was being subjected to vandalism, illegal subletting of shops, with shopkeepers and their assistants living and sleeping there at night, and there are also claims that many of them were armed. But the question is, why could the government agencies not look after this market and protect it from physical, social and environmental decay?

For the hawkers and small shopkeepers of Saddar, clearing the market and demolishing the shops is a part of a larger plan to gentrify Saddar. It is to take it away from them and hand it over to the developers. They claim that the plan is to turn Empress Market into an entertainment facility for an elite population that is eventually going to live in Saddar.

From the discussions above, it is clear that the street economy is an integral part of Karachi’s social and economic life and that, with an increase in Covid-induced poverty it is also increasing. Supporting it and its manufacturing and supply chain sectors with credit and technical support will increase jobs in addition to the economy itself.

Today there is a lot of talk about developing laws that regularise hawking. However, laws are complex things with minute details and procedures. They require bureaucracies and special agencies to supervise their implementation and they take time to enact. What we require is something immediate and hence very simple — allocate spaces where hawking can take place and survive, and hand over these spaces to the hawkers to maintain and stay within its limits, collect rent and deposit it in the government’s account. The rest can follow incrementally.

The street economy is also an integral part of Karachi’s tangible and intangible culture. Locations are known by the name of the food served there, by the products available there, and by the festivities (religious and secular) that take place there and all these are linked to Karachi’s street economy and its actors.

Heritage has to be seen in this context and where people own it and use it, it should be left to them.

Published in Dawn, EOS, January 3rd, 2021