Asian Inner Cities: Concerns of the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR)

In almost all cases the inner cities of Asia’s large urban centres consist of old walled settlements and the expansion around them in colonial times. By 1940, few of these cities were more than 400,000 population although by the 1920’s they contained major transport and cargo terminals (railway stations, ports and related functions) in addition to wholesale markets and storage spaces for them. They also contained the city’s commercial areas, housing for the elite and the merchant classes, and working class neighbourhoods.

After the Second World War, Asia’s major urban centres expanded rapidly and so did trade, commerce and industry. Many urban centres have since then become mega cities. However, in almost all cases plans for the expansion of the wholesale markets and their storage requirements, informal workshops and small-scale industrial activity, and the requirements of the transport sector that services them, were not planned and implemented. As a result, these activities expanded within the inner cities to engulf them completely. Most of the elite and merchant classes and the retail activity that catered to them, relocated to newly planned elite and middle-income settlements because of the physical degradation and the social changes that took place in the inner cities. In many cases the relocating population was replaced by migrant workers from the countryside. With further expansion of trade and related activities people from the newly established low-income peri-urban areas started to come to the inner city to work during the day time. As a result, important nodes of the inner city became transit areas for this population and hawkers established themselves in large number at these locations to cater to the transit population.

The result of these changes has been environmental degradation, stress on infrastructure, destruction of built-heritage, congestion, social fragmentation and in the absence of more favourable locations for warehousing and small-scale informal industry, rising landuse values for usages other than residential. The changes have also resulted in many community institutional buildings falling into disuse and disrepair as the community that built and managed them is no longer there.

Government plans for the inner cities normally consist of shifting wholesaling and small-scale industry to locations outside the city and removing the hawkers and gentrifying the areas that have been vacated. This process has been followed in Jakarta, Manila, Karachi and Bangkok. With the shifting of markets and industry the inner city population looses its jobs. In none of the new market and industrial relocations has provision been made for offering a housing option to the affected population at the new locations. Nor have urban renewal schemes attempted to cater to the social and economic needs of the resident population so as to prevent them from being forced to relocate. Studies reveal that this process of government planning has increased poverty.

Another aspect of government planning has been the building of expressways, roads and flyovers to solve the growing traffic problems of the inner city. These have displaced both populations and commercial activity with no alternatives being offered to the affected population. In most cases (Bangkok, Karachi, Manila), even the traffic problems have not been solved by the building of this infrastructure.

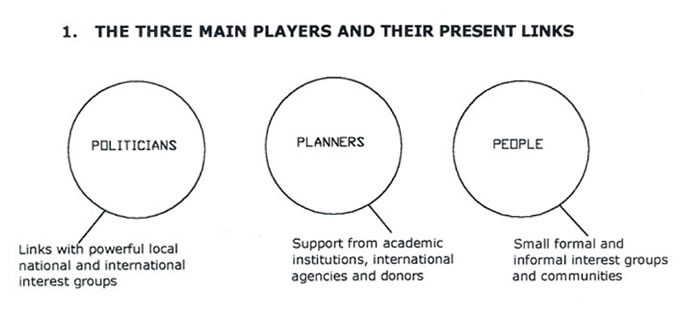

The ACHR feels that the reasons for this insensitive government planning are:

- The solutions that Asian governments are proposing and implementing are not a part of a larger city planning exercise. They are projects being implemented at different places without any coordination between them or with other projects in other parts of the larger city.

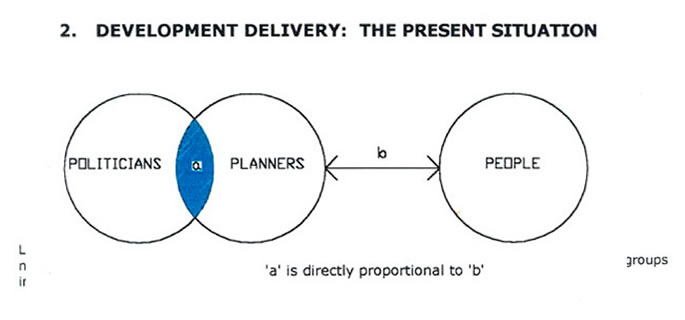

- Even where they are a part of a larger city plan, a powerful politician-bureaucrat-developer nexus sees to it that land value and not social and environmental conditions determine landuse. More recently international capital has become a part of this nexus.

- Inner city working class communities are politically weak and cannot negotiate with politically backed developers, contractors and mafias without professional and civil society support. Civil society support can only be generated if professionals can present alternatives based on participatory research.

- Professional organisations do not challenge these insensitive plans because their individual members and consulting firms are major beneficiaries of them. More recently, academic institutions have also become a part of this planning process.

- Architects and planners are not trained to make physical planning and technology subservient to social, economic and governance considerations. So even where they express concern on the insensitivity of plans, they do not possess the tools to offer alternative solutions.

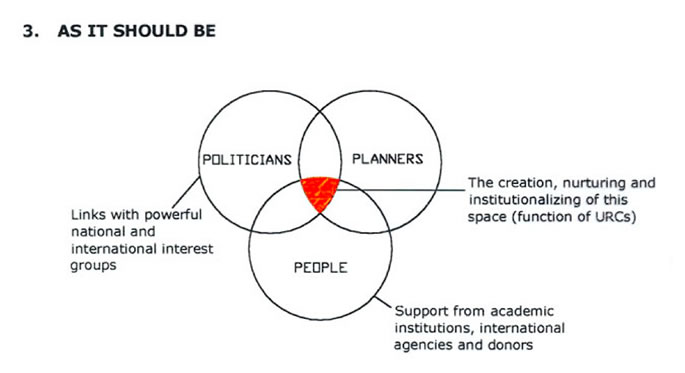

- Thus a key factor in dealing with inner city planning issues (or any planning issues for that matter) is appropriately trained professionals and a culture of consultation and consensus building.

In the case of Karachi, the Urban Resource Centre (URC), established by teachers of Architecture and Planning, NGOs involved in development and CBOs has made a difference. The URC collects information regarding the city and its plans and disseminates it to the media, NGOs, CBOs, concerned citizens and the formal and informal interest groups. It analysis plans from the point of view of communities (especially poor ones). On the basis of these analyses, it holds forums in which all interest groups, especially affected communities, are present so that a broad consensus may be attempted. The print and electronic media take up these issues. URC’s involvement has brought about many changes in plans for the inner city although it has not brought about a major shift in the planning process itself. The URC has been replicated through ACHR support in Phnom Penh, Colombo, Kathmandu and Cape Town.

The success of URC’s initiatives (however limited) is due to the fact that the architects and planners associated with and/or supporting it, were trained at the Department of Architecture and Planning (DAP) at the Dawood College in Karachi. In 1980 changes were made in the DAP curriculum. One of the changes was that in the final year a project known as the Comprehensive Environmental Design Project was introduced. The project consisted of dividing the class into four groups: i) Physical Conditions Group; ii) Economic Group; iii) Social Group; and iv) Governance Group. The groups were abandoned in a problem-ridden area of the city. Each group had to identify the actors of its subject and through dialogue with them understand the causes of the conditions in the area. The four groups then came together in a workshop and synthesised their findings. On the basis of these findings, individual students were asked to plan a physical intervention in the problem area which would benefit the community. A whole new manner of thinking and practicing planning and architecture emerged as a result.

Many of the graduates of this programme are now important persons. They are in government; they lecture at the institutions where bureaucrats are trained; they teach at different academic institutions and they write for newspapers and are interviewed on the media. They carry with them the one message which can bring about a positive change in the whole planning process of which the inner city issues are an integral part. This message is contained in the attached diagram and table.

The URC Reform Agenda

The Emerging Karachi Network

A. NGOs

- Orangi Pilot Project-Research and Training Institute

- Orangi Charitable Trust

- Aurat Foundation

- Shirkatgah

- Citizen’s Committee for Civic Problems

- Human Rights Commission of Pakistan

- Urban Working Group

- Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research

- Shehri

- Saiban

- Urban Resource Centre

B. 38 CBOs

C. Media Organisations

- Jung Forum

- ICN

- Press Club

- Manduck Productions

D. Interest Groups

- Minibus Drivers Associations

- Transport Ittehad

- Tanker Owners Association

- Karachi Bus Owners Association

- Solid Waste Recyclers Associations (6)

- Hawkers Associations (8)

- Kabari Welfare Anjuman

- Scavengers Associations

E. Government Departments

- Sindh Katchi Abadi Authority

- City Government Mass Transit Cell

- Karachi Public Transport Society

- Sindh Cultural Heritage Committee

- Karachi Master Plan Department

F. Academic Institutions

- Dawood College, Department of Architecture and Planning

- NED University, Department of Architecture and Planning

- Karachi University:

- Department of Architecture and Planning

- Social Works Department

- Mass Communications